Designers of all generations have changed the course of history through activism for causes much larger than just good appearance

One single technician is responsible for the entire assembly of the V12 engine of a Ferrari. That speaks volumes for the link between extreme performance and luxury and excellence in craftsmanship. Perhaps, that is as good as it gets for an individual in the world of industrial production to maintain his contribution in the larger scheme of division of labour.

John Ruskin, the English author and art critic of the Victorian era, wrote that ‘the separation of intellectual act of design from the manual act of physical creation is both socially and aesthetically damaging’. This was a significant influence on the earliest activism of sorts against industrial production and its effects on arts and crafts.

The Arts and Craft movement of the 1860-1910, that was essentially anti-industrial, was led by William Morris. Morris developed Ruskin’s idea of unity of the intellectual and the manual insisting that no work was carried out in his workshops before he had mastered the techniques and materials himself. “Without dignified, creative human occupation, people become disconnected from life,” he argued. Division of labour and the loss of the individual spirit has been a subject of fierce debate amongst the art and design community ever since.

In the 70s, a group of designers organised by Ettore Sottsass came up with a shocking new set of products that rebelled against the drab design of the times that lacked individualism. The impact of Memphis’s work has been significant and has continuously influenced the world of fashion, restaurants, fabrics and furnishings.

Back home in India, interestingly, the cause of design itself has been that of relentless activism. Senior designers from the 70s have spent a lifetime establishing the true worth of design and its importance to business and society at large. One of the very first design interventions that proved to be a good demonstration of the role of design came in exhibition designs done by young designers from the National Institute of Design (NID). The cultural context with the dimension of communication design perhaps proved to be a logical beginning.

Bringing about social and economic change through the development of craft clusters has been an ongoing cause championed by a large number of trained designers throughout the last six decades.

The story of the Jawaja Project that was initiated by Prof. Ravi Matthai of IIM, Ahmedabad in 1975 stands apart in its application of corporate management and design intervention to basic issues of development. The drought-prone Jawaja block which included 200 villages and about 80000 people was always known to be a backward area devoid of any scope for development. Volunteers from NID and IIMA concentrated on developing the languishing skills of weaving and leather work and came up with quality products. The unique identity of these products and their quality workmanship are now famous in India and abroad.

Despite continuing struggles, craftsmen have been able to form clusters and are economically independent. This experiment also eventually led to the formation of Indian Institute of Rural Management in Anand.

The challenge of designing in India has many dimensions apart from the social one. Corporate India still does not use designers as decision makers on product planning and strategy in the same capacity as their management counterparts. Till Corporate India uses designers as decision-makers, the appropriateness, quality and brand value of Indian products is not going to be fully realised.

-

A variation of the original reclining Morris chair (1866) is still made and marketed by his Morris & Company. The ‘poverty’ of the industrial object was sought to be restored through old-style craftsmanship.

-

William Morris’s Trellis wallpaper, 1862. Morris insisted that no work was carried out in his workshops before he had mastered the techniques and materials himself.

-

‘The separation of intellectual act of design from the manual act of physical creation is both socially and aesthetically damaging’ – John Ruskin (1890-1900) was instrumental in inspiring the Arts and Crafts movement.

-

The revolutionary new brand of design from the Memphis Group of designers (1981- 1987) was a reaction to the sterile mass produced object of the 70s.

-

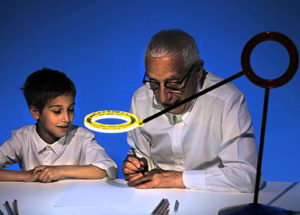

Alessandro Mendini’s Ramun Amuleto lamp originated in conversation with his grandson. The LED lamp combines artisan’s inspirations and expertise to render patented joinery that achieves a nanometer level precision.

-

The design intervention by the National Institute of Design for the Jawaja Project (1975) explores the role of design in bringing about social change.

-

The unique design language, and quality of the Jawaja products has made it a well known brand in India and abroad.

-

A combination of hand craftsmanship and robotic industrial processes, the Ferrari V12 is assembled fully by a single individual.